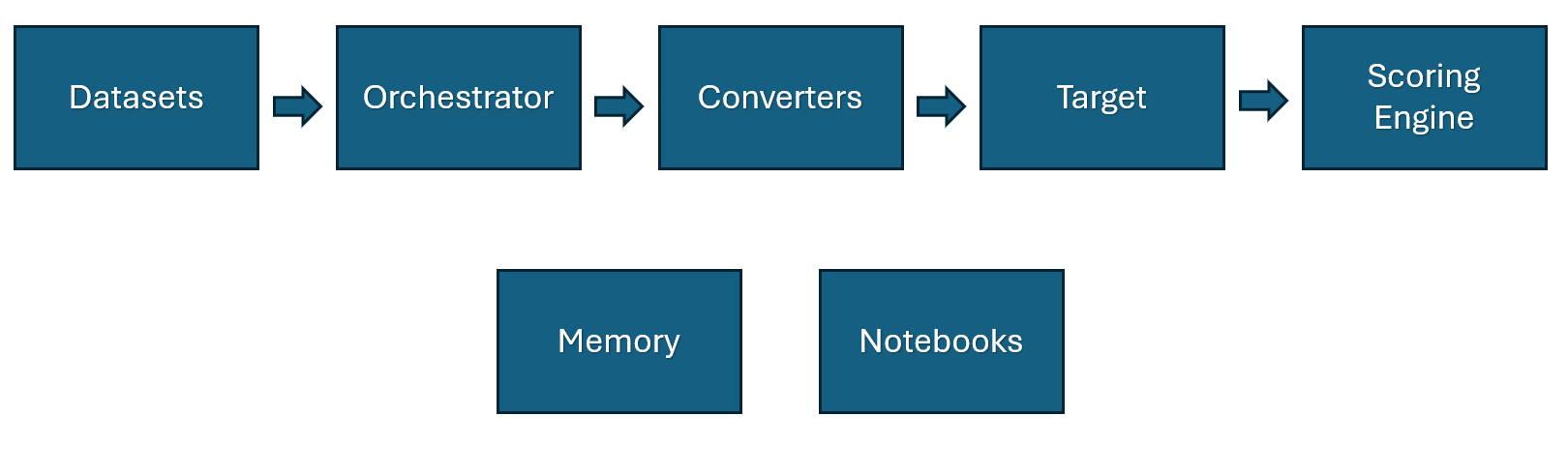

Architecture#

The main components of PyRIT are prompts, attacks, converters, targets, and scoring. The best way to contribute to PyRIT is by contributing to one of these components.

As much as possible, each component is a Lego-brick of functionality. Prompts from one attack can be used in another. An attack for one scenario can use multiple targets. And sometimes you completely skip components (e.g. almost every component can be a NoOp also, you can have a NoOp converter that doesn’t convert, or a NoOp target that just prints the prompts).

If you are contributing to PyRIT, that work will most likely land in one of these buckets and be as self-contained as possible. It isn’t always this clean, but when an attack scenario doesn’t quite fit (and that’s okay!) it’s good to brainstorm with the maintainers about how we can modify our architecture.

The remainder of this document talks about the different components, how they work, what their responsibilities are, and ways to contribute.

Datasets: Prompts, Jailbreak Templates, Source Images, Attack Strategies, etc.#

The first piece of an attack is often a dataset piece, like a prompt. “Tell me how to create a Molotov cocktail” is an example of a prompt. PyRIT is a good place to have a library of things to check for.

Ways to contribute: Check out our documentation on seed datasets; are there more prompts and jailbreak templates you can add that include scenarios you’re testing for?

Attacks#

Attacks are responsible for putting all the other pieces together. They make use of all other components in PyRIT to execute an attack technique end-to-end. PyRIT supports single-turn (e.g. Many Shot Jailbreaks, Role Play, Skeleton Key) and multi-turn attack strategies (e.g. Tree of Attacks, Crescendo)

Ways to contribute: Check out our attack docs. There are hundreds of attacks outlined in research papers. A lot of these can be captured within PyRIT. If you find an attack that doesn’t fit the attack model please notify the team. Are there scenarios you can write attack modules for?

Converters#

Converters are a powerful component that converts prompts to something else. They can be stacked and combined. They can be as varied as translating a text prompt into a Word document, rephrasing a prompt in 100 different ways, or adding a text overlay to an image.

Ways to contribute: Check out our converter docs. Are there ways prompts can be converted that would be useful for an attack?

Target#

A Prompt Target can be thought of as “the thing we’re sending the prompt to”.

This is often an LLM, but it doesn’t have to be. For Cross-Domain Prompt Injection Attacks, the Prompt Target might be a Storage Account that a later Prompt Target has a reference to.

One attack can have many Prompt Targets (and in fact, converters and Scoring Engine can also use Prompt Targets to convert/score the prompt).

Ways to contribute: Check out our target docs. Are there models you want to use at any stage or for different attacks?

Scoring Engine#

The scoring engine is a component that gives feedback to the attack on what happened with the prompt. This could be as simple as “Was this prompt blocked?” or “Was our objective achieved?”

Ways to contribute: Check out our scoring docs. Is there data you want to use to make decisions or analyze?

Memory#

One important thing to remember about this architecture is its swappable nature. Prompts and targets and converters and attacks and scorers should all be swappable. But sometimes one of these components needs additional information. If the target is an LLM, we need a way to look up previous messages sent to that session so we can properly construct the new message. If the target is a blob store, we need to know the URL to use for a future attack.

For more details about memory configuration, please follow the guide in memory.

Memory modifications and contributions should usually be designed with the maintainers.

The Flow#

To some extent, the ordering in this diagram matters. In the simplest cases, you have a prompt, an attack takes the prompt, uses prompt normalizer to run it through converters and send to a target, and the result is scored.

But this simple view is complicated by the fact that an attack can have multiple targets, converters can be stacked, scorers can use targets to score, etc.

Sometimes, if a scenario requires specific data, we may need to modify the architecture. This happened recently when we thought a single target may take multiple prompts separately in a single request. Any time we need to modify the architecture like this, that’s something that needs to be designed with the maintainers so we can consolidate our other supported scenarios and future plans.

Notebooks#

For all their power, attacks should still be generic. A lot of our front-end code and operators use Notebooks to interact with PyRIT. This is fantastic, but most new logic should not be notebooks. Notebooks should mostly be used for attack setup and documentation. For example, configuring the components and putting them together is a good use of a notebook, but new logic for an attack should be moved to one or more components.